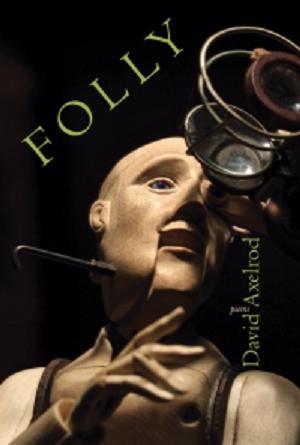

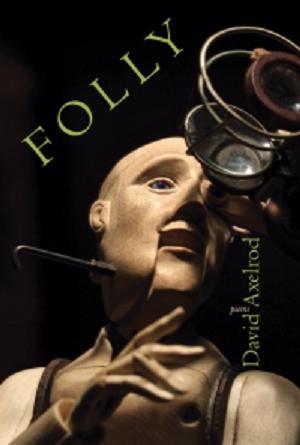

Micro Review of Folly, by David Axelrod

Lost Horse Press, 2014: $18.00 paperback

There’s a reason silence is a virtue; anytime we open our mouths, we just end up finding another opportunity to sound like an: “Idiot!” says Dostoyevsky, scolding the reader early on in “Skiing with Dostoyevsky,” the third poem of David Axelrod’s latest collection Folly. And of course we’re idiots to think we could keep up in a downhill race against a giant like Fyodorovitch: “One-hundred-eighty years old, give or take, and he’s skiing no worse today than he did a century ago.” But the question lurking underneath this poem (and this book) is both simple and rewarding: who gives a shit about winning a race that we all inevitably lose? And that’s why it’s so rewarding when, after the race is over, Dostoyevsky “pulls you chest to chest, so you can smell the pickles on his breath, see the silver flecks of herring between his teeth. ‘Are you listening to me, Duvy? Listen close,’ he says, and pats your cheek. ‘We live between torment and hope for mercy, though mercy never comes.’”

So what if Dostoyevsky didn’t actually say it (as far as my modest research revealed), it needed to be said. That’s what I found myself feeling again and again in this book—thankful that Axelrod has found new ways to make fresh the old knowledge we take for granted…that despite our foibles and shortcomings, at the end of the day we’re in this thing together. That failure is universal, even if the personal ones seem to be a reflection of our own unique design flaws. Like here, in the title poem, perhaps as poignantly as anywhere else in the book, the speaker has run out of water on a long hike, thinking foolishly that he would find a spring along the way:

So I sit down

in dust, perplexed, unable as always

to convince myself that I haven’t

squandered my life, drinking down

fantasies like nectar, fostering an insane

faith that it would come to something

other than so many of these dead ends.

But Axelrod rewards us again at the end of the poem with a surprise, a morsel of salvation—even if the word salvation is too big—“at the bottom of my rucksack—juicy, cool,/ and very sweet—this bag full of plums.” The reward for the reader is the same as the poet: that we have these words to share, these purely human moments to come back to and reflect upon—this shared theater of the absurd we call human existence.

—by Travis Mossotti