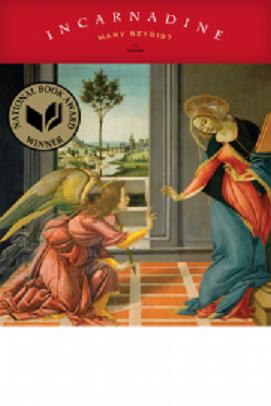

Micro Review of Incarnadine, by Mary Szybist

Micro Review of Incarnadine, by Mary Szybist

Graywolf, 2013: $16.00 paperback

Incarnadine is one of the quietest books of poems I’ve read this year—quiet in the way meditation is a quiet act—and the poems routinely resolve themselves through carefully constructed movements toward the middle of the path. The poem “Invitation” starts with the simple notion of believing in anything invisible: “If I can believe in air,” the speaker muses, “I can believe/ in the angels of air.” Whatever whimsical, childlike qualities these first two lines possess are rightly balanced when she goes on to invite the angels of abortion, alchemy, barrenness, bliss, earthquakes, forgetfulness, and so on, filling up the poem with the good and the bad this world offers, the pain and pleasure that fill us up, because, as the speaker concludes: “Without you my air tastes/ like nothing. For you/ I hold my breath.”

In James Wright’s poem, “Ars Poetica: Some Recent Criticism,” there’s a moment when the speaker says, “There must be something,” and I think Szybist tends to err towards this sentiment: belief in something without committing herself to a precise definition of what that something is. There’s room for question, doubt and even anger, and in “Holy,” Szybist gives us: “My mother is sick, and you/ cannot help her.// My beautiful, moon-faced mother is sick/ and you sleep in the dark edges of her shadow.” This initial observation gets complicated by revision, and that complication layers the difficult scene of her mother’s suffering with a pronounced frustration with a twinge of anger. The speaker grieves a dying mother through language and shows us the powerlessness of language to stop the inevitable we all encounter—how we do our best to make peace. Szybist is masterful at the balancing act, and her poems in Incarnadine (which jut from straight-forward lyrical narratives to concrete experimental) do a great job at balancing a wide array of expectations from her readers.

—by Travis Mossotti