Review of: The Red Riding Hood Papers, by Shanan Ballam

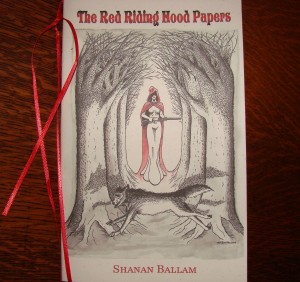

First things first—Finishing Line Press has crafted a beautiful chapbook with Shanan Ballam’s debut offering, The Red Riding Hood Papers. It’s a gorgeous object with great cover art, ensconced with black first and last pages, and mine even has a slim red ribbon tied snuggly against the binding, which can be used as a bookmark if you have to sit down more than once to read it through completely. But I wouldn’t suggest actually using it, because once you get started you’re going to want to see the story through to the surprisingly unpredictable end.

The story itself is bifurcated (as the opening poem suggests with its title “Both Sides of the Window”) so that it’s both a looking out and a looking in through the window of this very old, well-known German/French/Italian folktale: “The story is a window,” Ballam admits in the first line, which, after all, is the purpose of all folktale and myth—to be both story and metaphor. So when we turn the page to the second poem, “A New Beginning” (a poem in which an old woman talks the reluctant speaker into putting on the cloak and becoming her substitute granddaughter), the final five lines only work to reiterate this purpose:

I’ll admit, this premise could’ve worn thin pretty quickly if it wasn’t for poems that step out of the folktale’s familiar world and back into the speaker’s on the other side of the window (a world she seems hell-bent on escaping). Ballam is savvy enough to know this, and by the third poem, “The Porcupine,” she gives us a rough father figure, father who picks quills from the face of his hunting dog while his daughter straddles the dog, Saturn, to keep him pinned down: “Dad’s brown boot thudded into Saturn’s ribs/ clipped my heel hard, but I didn’t cry,” the speaker says with an almost calloused certainty. After the father leaves, kills the porcupine and brings it back home, the speaker delivers this emotional juggernaut of a tercet:

Moments like this one are so perfectly executed that they remind me of why I fell in love with poetry in the first place. Ballam is masterful at quietly and steadily forcing issues to a climax, condensing and focusing entire narratives into their ultimate emotional tenors. Again and again I’m left to pick myself up off the metaphorical floor, where my heart is left waiting, and move on to the next poem where it happens all over again:

…the last four lines from “Red Riding Hood’s Wish”:

…the last four lines from “Red Riding Hood and Wolf Discuss the Situation”:

…or the final two lines of the book from “Red Riding Hood Shoots Grandma’s Gun,” where the speaker takes target practice on a leaf and provides a certain kind of summation to the entire chapbook:

Maybe the inherent drama of this story (the undertones of sexual awakening and corruption mixed with humanity’s natural fear of the unknown) makes these moments even more poignant. At minimum, I think it’s the mark of a poet who knows exactly what she’s doing. Ballam too, is great at managing her poems rhythmically and sonically, and frequently infuses lines with end rhyme and internal rhyme. It helps keep her lines balanced, keeps the reader listening, and keeps the poem moving at a lively but controlled pace. Her deftness with language, her sharp turns of phrase, and her keen use of the line break carry us through each page of this chapbook as though we were reading a collection from someone comfortably in the middle of her poetic career. But she’s not in the middle, just begun really, right on the cusp, and I for one look forward to following her wherever she takes us next.