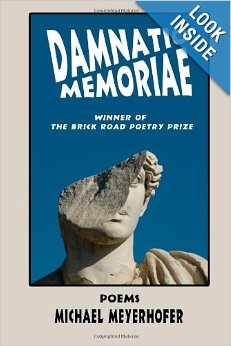

Review of: Damnatio Memoriae, by Michael Meyerhofer

classid="clsid:38481807-CA0E-42D2-BF39-B33AF135CC4D" id=ieooui>

Review of Damnatio Memoriae, by Michael Meyerhofer

Brick Road , 2011: $14.36 paperback

Michael Meyerhofer’s Damnatio Memoriae is one of those books I read about a year ago, enjoyed, put down, but never actually left alone. It sat in a wicker bin in my bathroom for months, followed me to class for a semester, and has done its best to resist being relinquished to its little sliver of shelf space.

To start with, there is a lot of real estate in this book (tops out at 100 pages), an ample offering, and the fact that this is only Meyerhofer’s third book makes that length something of note (edging closer into selected poems territory). The individual poems in the book aren’t long, never exceeding two pages, and they cover subjects as diverse as the world’s oldest dildo and the Winter Olympics.

Despite the length of the book and its ability to eschew a singular topic or focus, the curiosity, inventiveness and irreverence of the speaker(s) holds everything together—I’m thinking of the old Elmer’s glue commercial for some reason. Meyerhofer is savvy too though, and knows how to delicately weave practical and social impetus into even the most flippant premise. Take for example, his epistolary poem “To the President of the American Begonia Society,” which at first seems to be an occasion for the speaker to rail against something as absurd as begonias and those who cherish them:

Just think—the Great Depression

was all it took for Long Beach horticulturalists to get together

and coin the society motto: Stimulating begonia interest since 1932.

But the nod to the Great Depression does more than send the reader’s mind to a particular time and space—he’s talking about class and the things that distinguish such hierarchical distinctions:

Surely this beats my motto: Sweeping the leg since 1977,

an obscure reference to that classic 80s film, The Karate Kid—

These moments of unguarded honesty are both funny and poignant and they repeat themselves throughout Damnatio Memoriae—Meyerhofer, after all, wants the reader to know that he’s one of us; and by one of us, I mean this: fuck begonias and all other forms of dilettantism and dabbling—give me poetry or give me death. This poet is “Rolling at sundown into Hartford City, / home to a bowling alley turned lesbian bar / turned bowling alley, where drafts / lean into the soft fists of retired coaches, / feigning hope in tonight’s big screen blow-out,” and we’re all rolling along with him.

At times he reminds you of other notable poets (think Philip Levine/Dean Young hybrid), poets who have the uncannily easy way about the free verse line. He charges into narrative after narrative, lyric after lyric, with the same keen eye as those poets, and doesn’t back down when things get personal, as they do in Melancholia:

After my mother’s diabetes finally made me

half an orphan, my father and I drove north through

the white uppercuts of an Iowa snowstorm

to catch a plane to Fort Lauderdale,

then a cruiseship bound for the Bahamas.

The speaker finds no epiphany on the cruise, but Meyerhofer is confident that such an epiphany would’ve been cheap and wouldn’t have dulled the pain.

I came home the same. My father remarried.

My mother, whom I love, is still dead.

The mother comes back later in the poem “Mother’s Day,” still dead, and like most good books of poetry, you’re haunted by these moments, can actually feel something human clench up inside you as you course through the personal reveries. But there are also poems to his students, love poems to unrequiteds, an ode to dead batteries—anything, to Meyerhofer, is cause for a poem, and this idea manifests most poignantly in “Ode to Raccoons,” his version of an Ars Poetica:

When you asked what raccoons eat,

I said, Anything, they’ll literally eat anything.

In the poem they do eat anything and everything and convert it “into mother’s milk for a whole new gaze of raccoons,” as Meyerhofer puts it. In some ways, this is the most fundamental task of the poet. To take the otherwise indigestible material from the world and turn it into something of substance, something that can sustain us, and Meyerhofer does this brilliantly, which is the very reason that I’ve had such a difficult time putting this book back on the shelf.

—TM