12 Months of Essays on Poetry and Craft: April 2013 Vol. 5 # 10

The Light in the Darkness:

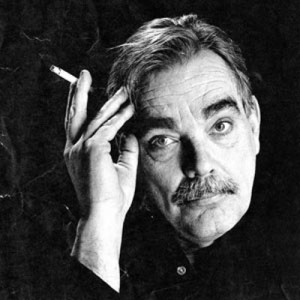

Misreading Larry Levis

By Timothy Shea

Date 4/29/2013

I first encountered the poet Larry Levis in graduate school. Standing in the stacks of another university’s library, I remember flipping Winter Stars open to the title poem and latching-on to what I thought was resentment toward his father for their relationship’s deficiencies. And as I encountered more of his introspective poems—what I came to call his Dark Night of the Soul poems—I was seduced by the meditative tone, focused only on it, and missed the range of human emotion that this tone can reach. Of course, if you’re guilty of misreading once, you’ve probably committed this crime countless times with countless poets. The result of my practice of misreading Levis ranged from a slew of poor imitations to, more severely, a misunderstanding of what I had read, and thus, faulty conclusions about his poetry and my thinking about the world. These errors began during a stretch of years in which I was in a prolonged down-and-out period. That is not the point of this essay, only the context for a practice that, my sense tells me, is not limited to feeling low-down. In fact, these errors occurred, I believe, due to a failure to surrender entirely to the poem I was reading. When I would come to a poet whose work I admired, I would not only look for what I wanted to be present in the poem (thus not recognizing what that poem was offering of its own accord), but I would frequently project my feelings toward that subject matter on his or her poem. It’s this idea, the reader hindering his or her understanding of a poem, which I hope to articulate with some examples of breaking this pattern of behavior.

I first encountered the poet Larry Levis in graduate school. Standing in the stacks of another university’s library, I remember flipping Winter Stars open to the title poem and latching-on to what I thought was resentment toward his father for their relationship’s deficiencies. And as I encountered more of his introspective poems—what I came to call his Dark Night of the Soul poems—I was seduced by the meditative tone, focused only on it, and missed the range of human emotion that this tone can reach. Of course, if you’re guilty of misreading once, you’ve probably committed this crime countless times with countless poets. The result of my practice of misreading Levis ranged from a slew of poor imitations to, more severely, a misunderstanding of what I had read, and thus, faulty conclusions about his poetry and my thinking about the world. These errors began during a stretch of years in which I was in a prolonged down-and-out period. That is not the point of this essay, only the context for a practice that, my sense tells me, is not limited to feeling low-down. In fact, these errors occurred, I believe, due to a failure to surrender entirely to the poem I was reading. When I would come to a poet whose work I admired, I would not only look for what I wanted to be present in the poem (thus not recognizing what that poem was offering of its own accord), but I would frequently project my feelings toward that subject matter on his or her poem. It’s this idea, the reader hindering his or her understanding of a poem, which I hope to articulate with some examples of breaking this pattern of behavior.

First, I would like to hone in on the types of poems to which I’m referring. The poems that struck me came in Levis’ final four books, The Dollmaker’s Ghost, Winter Stars, The Widening Spell of the Leaves, and Elegy. I don’t know if there is a term for the types of poems this essay discusses, so I will rely on the clarity of Tony Hoagland, who writes “again and again in the poetry of Larry Levis, a character will stop and stare, entranced—at a brick, at a river, at the grass, into space. What unfolds in that prolonged moment is a little piece of eternity—not a fixed infinity, but a shifting, permuting one. The moment becomes a sort of portal, in the frame of which the object of perception mutates under pressure of the gaze,” (485).

The poem, “The Wish to be Picked Clean,” resonates a desire for nothingness. This is not a poem that Levis wrote, I assume, after a night of great partying. The poem is as deceptive as the world is deceptive. We are presented with many specifics—“a dead spider on the sill,” “the air of a struck chord,” a black man’s unmatching socks “one a fading gold, / one white,” the veins on the man’s hands, the Ohio River—but the poem has no place. It is set in no specific location. It occurs only in the mind, sprung from a feeling of wanting something. And the poem deceives us by moving, from time to time, away from the cold, objective tone of the line “I was nothing, then” and toward a humor and lightness that is sparse, subtle, and which I missed completely for years.

The first line is “I still oversleep these winter mornings.” Later he wants “a stillness in the wake of each thing.” Then he says that he “wanted, once, to be picked clean by music, / by wind, by sunlight.” Sitting in the stacks of that library, seduced by this serious, hard-staring tone, I read these lines and said, yes, Larry. I feel that way all the time. You’re a low-down son-of-a-bitch like me, aren’t you, Larry? The poem continues:

I would stand outside in the winter dusk,

I would think

Of those extinct Scottish poets

Who placed stones on their bare chests

And then laid down in snow each night until

The right poem came.

They praised, always, the hard ways of their Lord;

Because we’ve been lulled into the poem’s surrender and solemnity and empathize with the metaphor of this human being standing in the elements until whatever it is he’s looking for comes to him, it’s easy to miss the humor in the next lines:

Their grins frightened even

their wives…

In one of the essays in The Gazer Within, Levis’ essays on poetry, he writes about how, as he began writing longer narrative poems, he broke lines on articles and weaker words as a device to move the reader down the page. However, now I read less importance into line breaks or the half-meaning that the Scottish poets were so grizzled and scary that even their grins were frightening, than I do into the line “Their grins frightened even” as the joke’s setup forcing the reader to move to the next line for the payoff, “their wives.” Because I was treading water in the sea of simple, all-or-nothing cognition that I was at the time, the notion that one could find humor in anything while contemplating a serious personal matter was non-existent to me. Not only was I missing the poem’s humor and a piece of this poet’s charm, but I was also perceiving this poem from a faulty logical foundation, and missed the self-awareness in this moment of the poem. The joke that the Scottish poets’ are ugly enough to scare their own wives demonstrates that Levis recognizes the futility in his wish for anything. Once he arrives at this humorous realization, he begins to spiral back toward the poem’s original tone, but that tone rarely, if ever, sinks to the despair with which the poem began. Instead, the poet recognizes the significance of a moment of intense consciousness:

It took me fifteen years to learn

How not to pray,

And tonight I toast a blind, black man

With a cane,

Who I met, once, in Louisville.

Whose socks were unmatching: one a fading gold,

One white.

It was humid in the park,

And he sat there,

Smiling at each thing I said.

I thought he liked the feeling of the sun

On his face, or on his hands,

Or that he liked my company.

I learned, later, that he was simply terrified,

And that a gang of boys had crept up, earlier,

With sticks—

I was too young, then;

I was nothing, then

He nears the original tone is those last two lines, but he has moved to the past tense. “I was too you, then; / I was nothing, then,” is a reflective statement, not the declaration of the poet’s misfortune as we see at the beginning of the poem. But all does not end in the depths of sorrow, as Levis casts some light on the blind man. “If I could imagine him now,” he writes, “picked clean / and without pain…”

It would be easy,

It would be a wind no thicker than your wrist

Over this page, or the music of wind

“The Two Trees” is another poem that rises out of a sense of dejection, alienation, disenfranchisement. Here we have a middle-aged man who is staying out to “read late in the library,” where “the black windows looked out onto the black lawn.” The tone has been set. Levis, a poet whose facility for description is as good as they come, has gone negative again, and calling out to Dante, the poem continues:

Friends, in the middle of this life, I was embraced

By failure. It clung to me & did not let go.

When I ran, brother limitation raced

Beside me like a shadow.

And later:

My head ached.

And I would walk home in the blackness of winter.

This is not a portrait of a family man who hurries home to get little Larry to the soccer field. This is a man who comes and goes as he pleases, who frequently eats alone. If this poem were a scene in a film, we’d meet our character as he is exiting the library. But before opening the door, he’d stop to raise his raincoat’s zipper to his chin or pull its hood over his head, and then he’d step outside onto a quiet city street of minimal traffic and light rain in that three-quarter-slow-motion speed that filmmakers like Wes Anderson employ—the audio of Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” fading in.

We’re into another meditative, contemplative Dark Night of the Soul walk. “Everything I have done has come to nothing,” he tells his two friends, who are the trees. “It is not even worth mocking.” And then, in direct retort to that statement (and to himself, because the easiest way for a poet to say something about his- or herself is to make someone else say it), one of the trees replies, “You do not even / have a car anymore.” So wrapped up in a combination of my own emotional turmoil and reading inexperience, I was unable to swim out of the poem’s low-down tenor and climb to a safe, critical vantage point, and thus I missed the hilarity present here: a tall, lanky, mildly hunchbacked but completely mustachioed poet talking to and receiving feedback from a box elder and a horse chestnut in Utah. But what is important to note here is that, after a bit of light, the poem’s focus becomes external:

In time, in a few months, I could walk beneath

Both trees without bothering to look up

Anymore, neither at the one

Whose leaves & trunk were being slowly colonized by

Birds again, nor at the other, sleepier, more slender

One, that seemed frail, but was really

Oblivious to everything. Simply oblivious to it,

With the pale leaves climbing one side of it,

An obscure sheen in them…

Failure, shadow, black, blackness, late, limitation, winter: for years I would lie on the floor of my apartment reading this poem and I would have a similar experience to when I listened to Otis Redding sing. And this seems to me the crux of my misreading, and one of the elements that highlights Levis’ literary abilities: his tone will seduce you, but the range of human experience is always there, too. If one opens “The Two Trees” and feels instead of reads, one will encounter an pathos of such depth that one will be transported into a great soul music album. If, however, one brings a critical eye to the poem, the classical allusions to Ovid’s Daphne and Apollo, and to Dante’s middle-aged journey through hell are that of a learned, daring scholar and maker of elegy.

Before discussing Levis’ father poems, I need to depart, briefly, to touch on the severity of this next element of my misreading. To misread a poem as a result of inexperience is excusable and to be expected, but to simply insert oneself into a poem and assume knowledge of that poem’s intellect, humanity, and emotional depth is in direct violation of that poem’s autonomy, and it seems, a violation of oneself. Even if poems are not autonomous things, to read closely is to listen closely, and in that way, a reader who projects his or her emotional baggage onto a poem cannot fully listen to or be with a poem. At the time I encountered these poems, I was writing a good deal about my father, who shares the qualities of silence and stoicism that Levis attributes to his father. So when Levis described his father’s emotional distance, I assumed the poet was, like me, resentful, when in fact he was forgiving or desiring reconciliation. The reason this practice is so harmful to a reader is not that you misunderstand what you’ve read, it’s that you’re blind to a human perspective from which you could gain a greater understanding of yourself.

The first two examples of light in Levis’ work occurred in poems about the current state of his life, and the light arrived in the form of subtle humor or self-deprecation (or both). The second type of light that I missed occurs when he writes about his father, and that light exists in the form of forgiveness. “To a Wall of Flame in a Steel Mill, Syracuse, New York, 1969,” opens with things disappearing. The snow is thawing, and the poet’s father, who “longed to disappear,” desires “to be grass, / and simplified.” His thoughts move “like the shadow / of a cloud over houses.” There is significant emotional space between speaker and father. I resented that space for many years, and as a result of that resentment, I missed the gratitude in:

But in the long journey away from my father,

I took only his silences, his indifference

To misfortune, rain, stones, music, and grief.

Now, I can sleep beside this road

If I have to,

Even while the stars pale and go out,

And it is day.

In those six lines, Levis expresses that while there were elements of their relationship that were missing, there were also essential skills that his father displayed to him and which the poet benefitted from: toughness, resiliency, contentment from within. There is a world of humanity present in this gesture, and my failure to recognize it during my early reading was a direct reflection of the absence of this gesture in my own life.

The title poem of the book Winter Stars is perhaps the most telling, and therefore the most embarrassing, example of my misreading. After all, the final two lines are “Cold enough to reconcile / even a father, even a son.” When I first came to this poem I focused on the single line “When I left home at seventeen, I left for good,” and I felt anger and disappointment. Looking at this poem now, I see forgiveness, a desire for resolution, and recognition that not all relationships are defined by the language shared between two people. The poem’s opening scene has a man named Ruben Vasquez trying to kill his own father. Levis’ dad intervenes, breaks Ruben’s hand, and then goes inside, saying nothing of it:

When it was over,

My father simply went in & ate lunch, & then, as always,

Lay alone in the dark, listening to music.

He never mentioned it.

Ironically, we then learn that:

In a California no one will ever see again,

My father is beginning to die. Something

Inside him is slowly taking back

Every word it ever gave him.

Now, if we try to talk, I watch my father

Search for a lost syllable as if it might

Solve everything…

During those weeks in which I first read this poem, I was looking at pages ten and eleven of Winter Stars and, at times, I was even saying the words out loud. So how could I have executed such poor reading on a relatively straightforward poem? All I can say for sure about this experience is that if listening completely is a state of being, then I was nothing. Once, I stopped reading after the lines “I stand out on the street, & do not go in. / That was our agreement, at my birth.” But what I missed was:

And for years I believed

That what went unsaid between us became empty,

And pure, like starlight, & that it persisted.

I got it all wrong.

I wound up believing in words the way a scientist

Believes in carbon, after death.

And then:

That pale haze of stars goes on & on,

Like laughter that has found a final, silent shape

On a black sky. It means everything

It cannot say.

The telling word here is cannot. Michael Longley once said that a poet should take what he or she has learned at the end of a poem and apply that to the beginning. Taking that advice, this is a poem in which Levis forgives his father for being a distant man of few words by layering images of speechlessness. Another way of putting it is that you can have a great deal of love for a person to whom you rarely speak. Once I was able to see that, this poem began to glow as brightly as the city in the poem’s fourth stanza, a city that is “placed behind / the eyes, & [is] shining.”

I remember standing in the middle of my wife’s living room early in our dating days, and relishing in the cleanliness of the place. It had been dusted, the hardwood floors had been scrubbed with white vinegar and the scent persisted. Clean lines abound. Colors matched. And outside, an impressive flower garden immaculately arranged and cared for: buddleia, peonies, zebra grasses, black-eyed susans. Flowerbeds she designed, dug, and lined only with aged bricks stamped with town names, business names, the names of railroad lines. At a party in that yard I once heard someone say that the garden was so clean, all the bugs must have moved into the house. Of course, as time passed, I gathered a more complex definition of her, and I came to know the woman who often leaves crumbs on the counters, dishes for me to trip over in awkward places, who is as human and error-prone as us all. And I only loved her more. This is not to say that I fell in love with her because she kept things tidy, there are many other reasons of character, beauty, humor, and vision, but early on I found the orderliness an attractive quality. I fell in love for, partially, flawed reasons, and I still loved after coming to know more fully. This is the scenario I find myself in with the poetry of Larry Levis. When I came to his poems, I was in something of a trance state, and I reacted to his meditations. I was self-absorbed and projected my feelings on his subject matter. But as I continue to read these poems, I come to know a multi-faceted poet capable of humor, sorrow, meditation. I come to know a poet who isn’t afraid to plumb the depths, and then to light the way.

_____

About the Author:

Timothy Shea holds degrees from Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia and Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He has also studied at the National University of Ireland Galway and at the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at Queen's University Belfast. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry London, Third Coast, Southern Humanities Review, and Poetry Ireland Review, amongst others. He lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Timothy Shea holds degrees from Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia and Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He has also studied at the National University of Ireland Galway and at the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at Queen's University Belfast. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry London, Third Coast, Southern Humanities Review, and Poetry Ireland Review, amongst others. He lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.